Engineering the invisible - A day at RTU IPET

Have you ever wondered what exactly happens when you double tap a post on Tiktok? When you call someone, do you wonder how your voice gets transmitted across these massive distances? Or what those Eiffel-tower-looking things you see on the street are? Do you wonder why that guy from the Wi-Fi company keeps nagging you to install optical fibre?

Well, we did wonder, and we found all our answers and much more at the RTU Institute of Photonics, Electronics and Telecommunications (IPET). Across the many laboratories we visited, we saw things that we could only theorize being continuously tested against reality, and ideas being refined to experiments with real-world impacts of unimaginable calibre.

We started off by talking to Researcher and PhD student Chen Tianhua about the IPET’s latest and most exciting endeavour: Open RAN.

Open Radio Access Network (or, Open RAN), is a method of making cellular networks open source. At present, the Radio Access Network is largely a closed (proprietary) segment of mobile infrastructure. Telecommunications providers typically purchase RAN equipment from only a small number of vendors, each offering tightly integrated hardware and software solutions. This structure leaves little room for flexibility, as third parties are effectively locked out of providing individual components of the system.

Open RAN seeks to challenge this model. As Tianhua puts it, the goal is to “break this blackbox” by separating software from hardware. In practice, this means that different parts of the network can be supplied independently, allowing for far greater customization and control. Networks can be tailored to specific needs rather than built as one-size-fits-all solutions. This will also drive costs lower, as the competition between vendors for an open market calls for price appeal. This shift has reaches even in business and government: enabling small players like startups to apply their innovations without extensive cost and giving public institutions a larger oversight in areas tied to national security.

The benefits extend from economic to geographic as well. Open RAN is not limited to dense urban environments. Through the use of vRAN (virtual RAN), functions can be run on software hosted remotely. This reduces the need for extensive on-site hardware, making it possible to deploy networks in locations that were previously untapped such as rural regions and mountainous terrain.

In a world increasingly dependent on connectivity, this transparency could prove just as important as speed.

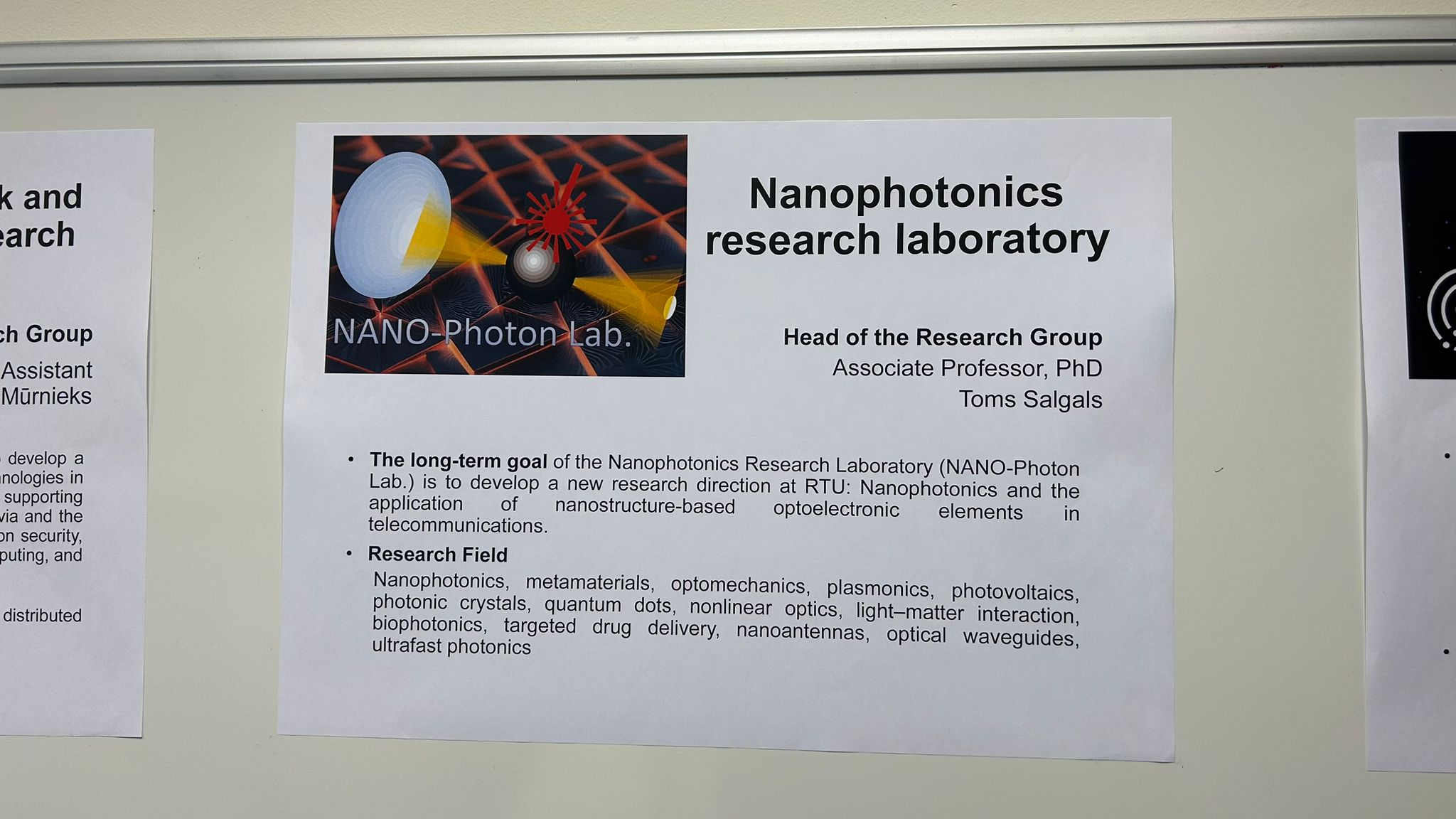

After that we headed to the lab that started it all — the Nanophotonics scientific laboratory (NANOLab). Here we were greeted by Dilan Ortiz, who is also a researcher and PhD student.

The word photonics first appeared in the late 1960s. Interestingly, one of its earliest uses is attributed to John W. Campbell—the father of modern science fiction. He described photonics as a branch of optics bearing the same relationship to it as electronics does to electrical engineering. Unlike traditional optics, which primarily studies the behavior of light through macroscopic components like lenses or mirrors, photonics focuses on controlling light particles at microscopic and nanoscopic scales. It enhances a wide range of engineering fields including but not limited to telecommunications, medicine, quantum computing, and renewable energy.

The NANOLab made all these ideas tangible from the very start as we were handed a vial of photons, sized around 4nm, suspended in alcohol, and shown the magnified images of the particles and what disrupting them actually means. When asked, Dilan told us that understanding the movement of these particles consists of, most essentially, calculus.

Dilan went on to explain the applications of this technology in targeted drug administration and organic tissue removal, pulling us out of the stupor of Maxwell’s equations and into the extensive biomedical importance of photonics. He told us about its uses in the military for fast, lossless telecommunication, and an experiment involving drilling a hole into a fibre to split a beam of light and create two beams with the power of one.

By the end of our time at the NANOLab, it became clear to us that photonics was not simply about studying light, it was about engineering it to become a tool capable of meeting the increasing demands of faster data transmission and lower energy consumption

Now, taking a leave from the sciences for a bit, the IPET is RTU’s largest institution. A staunch research centre, it is brimming with a community of Bachelor’s, Master’s and PhD students, research assistants, professors and the like. The community is increasingly international as well, as both Tianhua and Dilan speak fondly of their experiences as international students from China and Colombia respectively. The entire institute also works closely with each other, as cited by Daniils Surmacs, another researcher and PhD student we spoke to. We experienced firsthand the warm welcome of this close-knit faculty thanks to our wonderful tour guide Natalija Muracova, the Deputy Director of IPET.

By Misha, Aleksandrs, Emils, Hugo, Susanna and Bheeni.