Microbes, Membranes, and the Future of Water

A visit to RTU’s Water Systems and Biotechnology Institute

At first, the Water Systems and Biotechnology Institute at Riga Technical University does not look like a place where big world problems are being solved. But behind its lab doors, bacteria clean dirty water, plants help reduce flooding, and engineers build their own scientific machines. Here, scientists study dangerous microbes in hot water systems and turn waste into things like cat litter and even biofuel. It is a place where biology and engineering come together to protect people and nature.

From one lab to a full institute

The institute started almost 20 years ago. Its first laboratory was opened in 2005, long before environmental biotechnology became popular.

2005-2026

One of its most important early projects was studying Legionella bacteria. These bacteria live in hot water systems and can cause serious lung illness when people breathe in water vapour, for example from showers.

Linda Mežule and her team were the first in Latvia to properly research this bacteria. They discovered that Legionella can survive even in water that is not very hot. Because of this, water system designs were improved, making buildings safer and helping protect public health.

How the research works

People here almost never work alone. Teamwork is very important.

Most projects depend on funding, mainly from the European Union, so the institute often works with other European research centres such as, Netherlands, Sweden and Norway. They also cooperate with partners in India and Latin America, and sometimes with researchers from the USA or Australia when possible.

Usually, there are about ten research projects running at the same time. These are paid for by:

- research grants,

- cooperation with companies,

- consulting work,

- testing projects with water and wastewater companies.

Sometimes companies even give equipment or help build test systems, even if they are not official partners.

MikroTik and Watex gifts for lab

Inside the laboratories

During our visit we saw how carefully everything is organized. Clean labs are kept separate from bacteria labs to avoid contamination. There are also teaching labs where students use the same equipment as real researchers.

In one lab, a PhD student was working on membrane technology, testing how to make membranes last longer and resist bacteria in water treatment systems. Even though the institute prefers natural solutions like plants and microorganisms, membranes are still very important.

In another lab, we noticed a strong and strange smell. It came from an experiment making cat litter from waste for a startup company. The researchers were mixing materials with simple tools like sticks and ladles, showing that you do not always need expensive machines to do serious science.

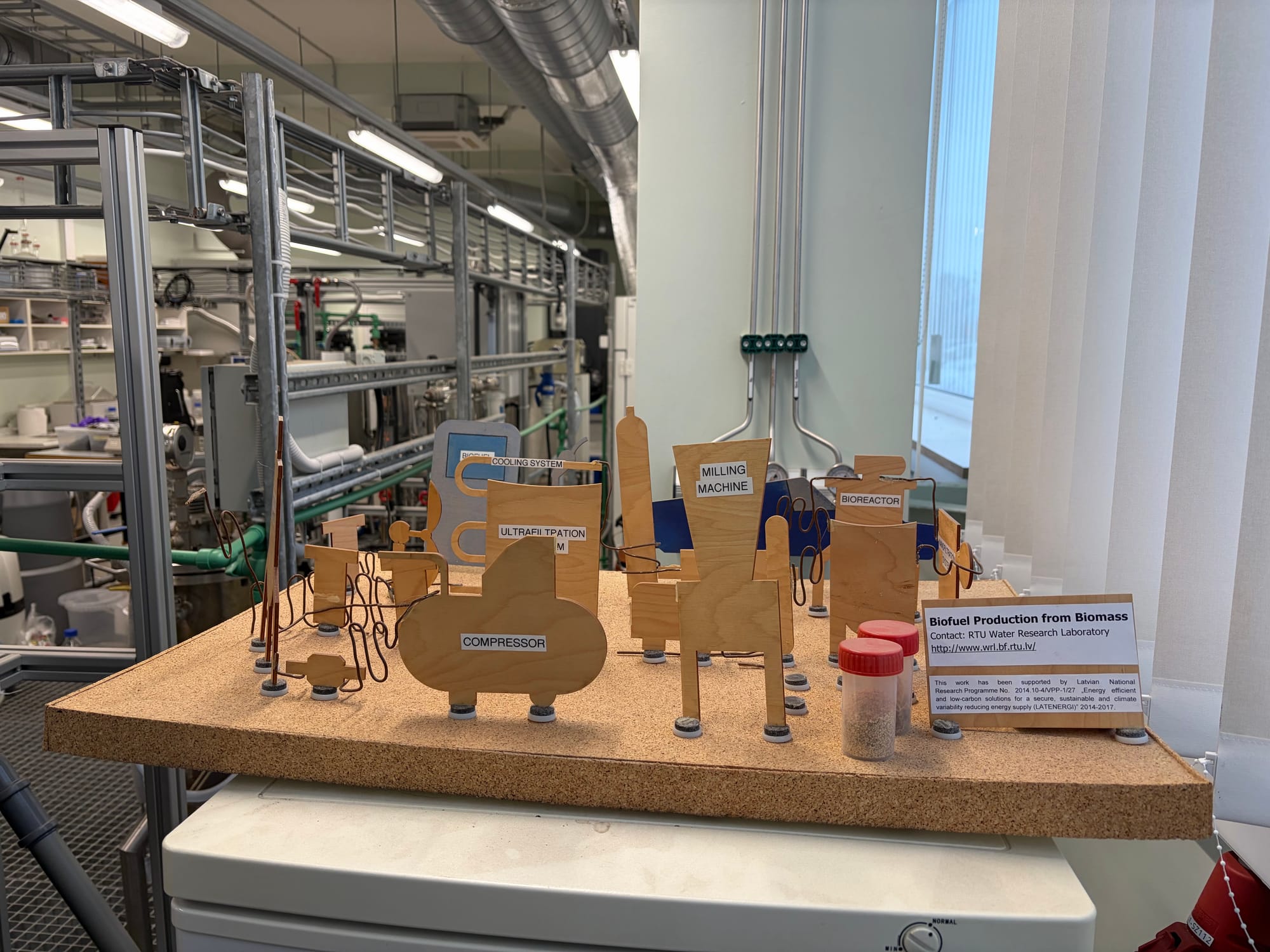

To help visitors understand the lab layout, the staff even built a small wooden model of the room, showing where the machines and ventilation systems are placed.

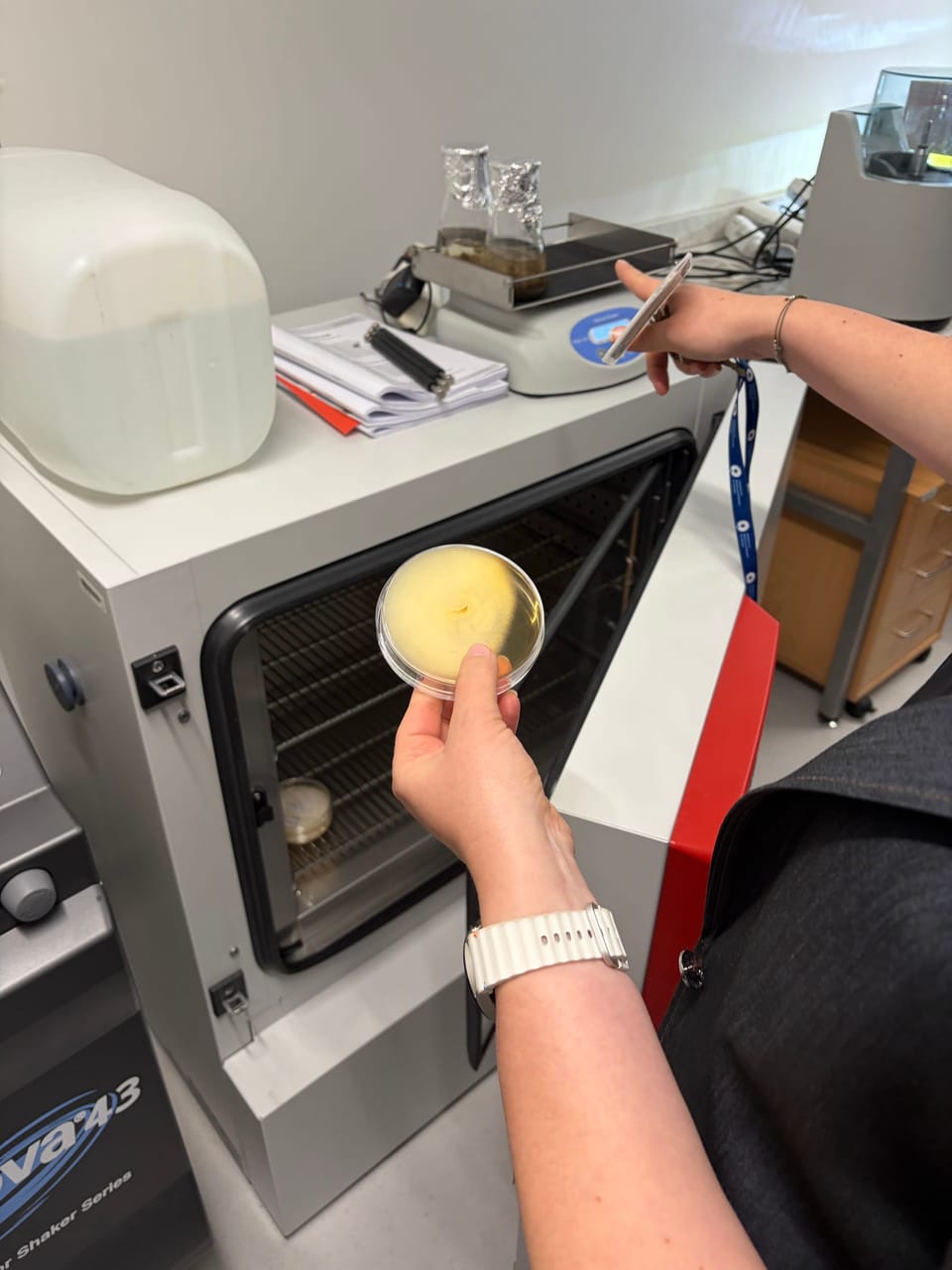

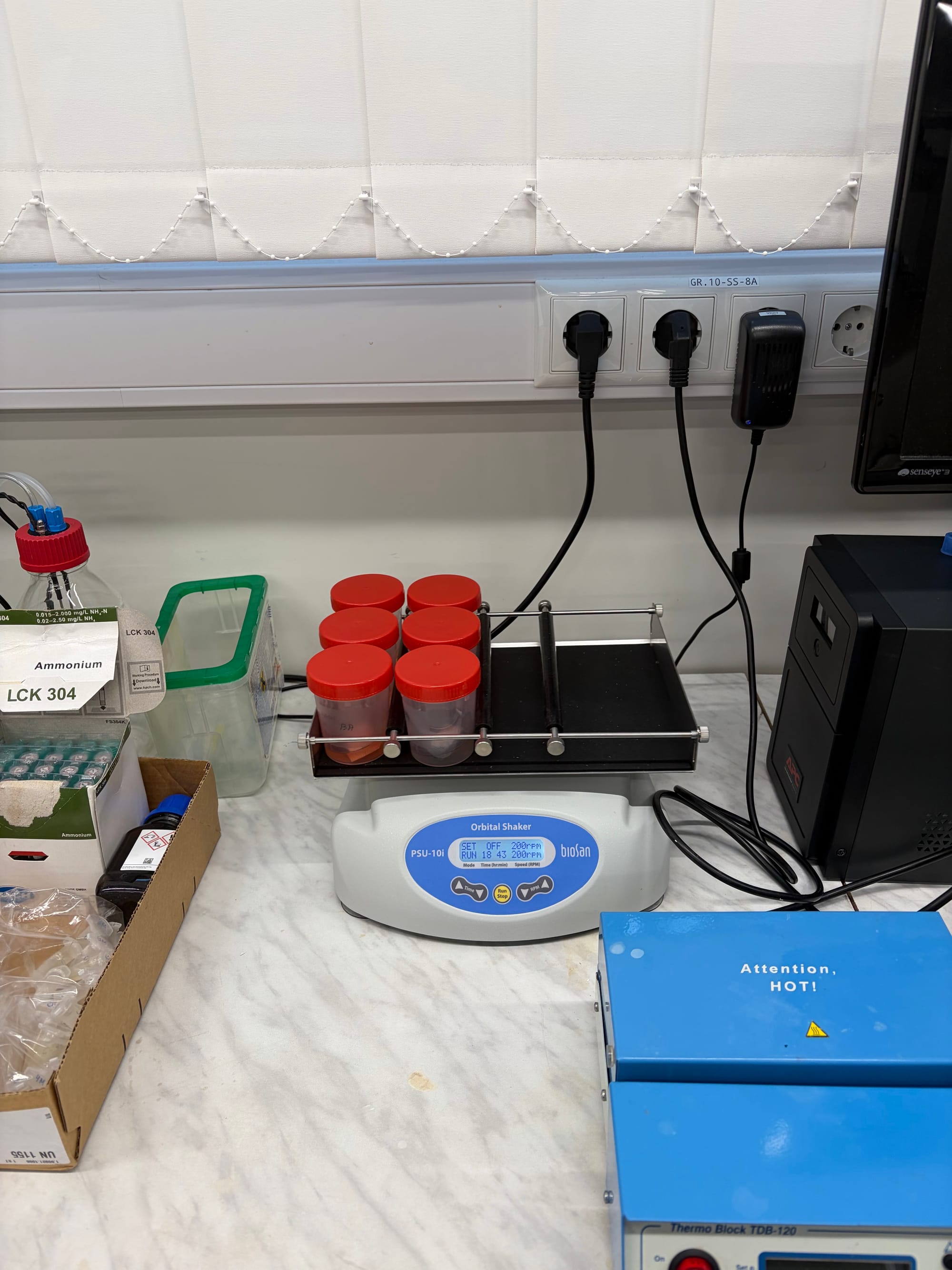

We also saw how researchers grow microorganisms to make enzymes in the lab. These bacteria and fungi are kept in special containers where things like temperature, light, oxygen, and food are carefully controlled.

The enzymes they produce are later used to:

- break down pollution in wastewater,

- remove nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus,

- help make biofuel,

- and improve other biotech processes.

The researchers told us that using living microorganisms to produce enzymes is usually cheaper and better for the environment than making enzymes with chemicals. It also lets them adjust the process for different kinds of waste or water pollution depending on what the project needs.

One funny detail showed real lab life: the ventilation is so strong that the door must stay open, but safety rules say it should be closed. The solution? The door is kept open with a chain and locked at the same time.

Building their own equipment

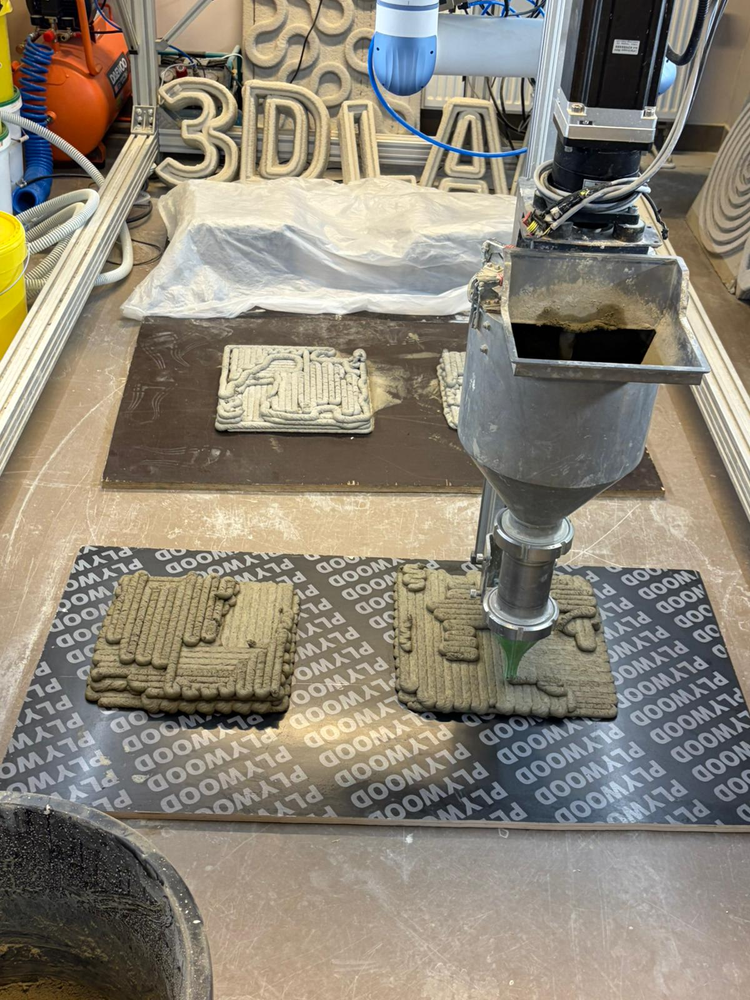

Because money and space are limited, the institute often builds its own machines instead of buying expensive ones. Engineers and programmers use sensors, cameras, LED lights, incubators, and software to create custom systems for experiments. This makes research cheaper and more flexible.

Still, some machines cannot be replaced.

One of the newest devices is a DNA sequencing machine called the iSeq 100 from Illumina. It costs around 50000 euros, and each test costs about 1,000 euros because of special materials. The staff jokingly call it “Bob” ,giving a human name to one of the most advanced machines in the lab.

"Bob"

Students are part of the team

Students do not just study here - they really work.

Bachelor’s, master’s, and PhD students take part in real projects together with professors and engineers. The institute has around 35 to 40 people, including five professors and several doctoral students.

Teams often include students, teachers, industry experts and visitors from other countries.

Many graduates later work in biotechnology, medicine, cosmetics, environmental engineering or water management, both in Latvia and abroad.

Turning waste into useful things

Another important research area is turning waste into something valuable.

Scientists take grass and other plant waste, turn it into sugar, then use bacteria or yeast to make ethanol or butanol, which can be used as fuel. The process works well, but it is complicated and needs careful chemical treatment and cleaning.

In the future, they want to expand this work to:

- bioplastics,

- better fermentation products,

- full systems that turn waste into useful resources.

They try to avoid harmful chemicals and focus on eco-friendly solutions.

Conclusion

The Water Systems and Biotechnology Institute may not be the biggest lab in Europe, but it is definitely one of the most practical and diverse. Scientists here mix biology, chemistry, engineering, and programming to solve everyday problems like clean water, safe buildings and sustainable materials.

From bacteria in hot water pipes to a DNA machine named Bob, from waste-based cat litter to students testing water filters, the institute shows how modern science really works: together, creatively and with real impact on the world.

Article by Ksenija Rašale, Arsenijs Krasovskis, Kārlis Avotiņš, Martins Mašals, Artemijs Baltmaķis, Annija Vilde