Bones and Beyond: Inside the Baltic Biomaterials Centre of Excellence

A white-coated researcher holds up a small unlabeled tablet, jokingly calling it a “secret bone pill.” Nearby, a life-sized skeleton named Johnny leans against a gleaming lab bench, as if supervising the scene. It’s a typical afternoon at the Baltic Biomaterials Centre of Excellence (BBCE) in Riga – a place where high-tech experiments in bone regeneration unfold amid quirky lab culture. From an occasional popping test tube (the byproduct of an overzealous liquid nitrogen demo) to the unassuming grey boxes that hide powerful microscopes, the atmosphere swings between the mundane and the marvelous. Yet behind the lighthearted touches, BBCE’s scientists are deadly serious about their mission: turning today’s lab discoveries into tomorrow’s life-saving implants.

Laying the Groundwork: A History Forged in Bone

The BBCE’s story begins long before its official launch in 2020. Its roots trace back to the mid-2000s, when visionary Latvian chemist Prof. Rūdolfs Cimdiņš spearheaded the creation of a biomaterials research center at Riga Technical University (RTU). In 2006, RTU opened the Rūdolfs Cimdins Riga Biomaterials Innovation and Development Centre (RBIDC) - Latvia’s first major bone technology lab - with support from the EU PHARE program. Prof. Cimdiņš, alongside Dr. Līga Bērziņa-Cimdiņa, laid the foundation for Latvia’s biomaterials science nearly two decades ago. (Tragically, Cimdiņš passed away days before the RBIDC opened, but his legacy would set the stage for what was to come.)

Fast-forward to January 29, 2020: the Baltic Biomaterials Centre of Excellence was formally inaugurated as a new joint research hub, uniting multiple institutions under one umbrella . The President of Latvia, Egils Levits, attended the opening ceremony, hailing it as a “milestone for our scientific community” and predicting a €74 million economic impact over 20 years. Backed by a hefty €30 million in funding (half from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Teaming grant, matched by national and partner contributions), BBCE was charged with an ambitious purpose: to connect lab-bench research to clinical bedside applications.

From day one, BBCE was envisioned as a collaborative powerhouse. RTU (with its materials chemistry expertise) joined forces with Rīga Stradiņš University (RSU, home to medical and dental researchers) and the Latvian Institute of Organic Synthesis (LIOS, experts in pharmacology) – plus two renowned Western European partners, the AO Research Institute in Davos, Switzerland, and the Institute of Biomaterials at FAU Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany. This international team set out to cover the “full cycle of a biomaterials pathway from laboratory to clinics”, allocating each partner a role: RTU on material development, LIOS on biological testing, and RSU on clinical translation. By integrating what had been fragmented research efforts across different sites, BBCE hoped to avoid duplication, fill innovation gaps, and accelerate breakthroughs in regenerative medicine. As BBCE’s first few years unfolded, it began to fulfill that promise – establishing new labs, hiring young scientists, and aligning Latvian research with global cutting-edge science.

Scientific Focus: Designing “Human Spare Parts”

Walk into BBCE’s brand-new headquarters on RTU’s Ķīpsala campus and you’ll see what researchers enthusiastically call “making human spare parts”. The Centre’s core scientific focus is on advanced biomaterials for bone and tissue regeneration. In practical terms, BBCE scientists design materials that can repair or replace damaged bones – think synthetic bone grafts, bioactive coatings for implants, and porous scaffolds that help new tissue grow. The notion sounds futuristic, but it builds on a simple idea: if a bone in your body gets damaged, why not create a replacement that your body will accept as if it were a part of you?

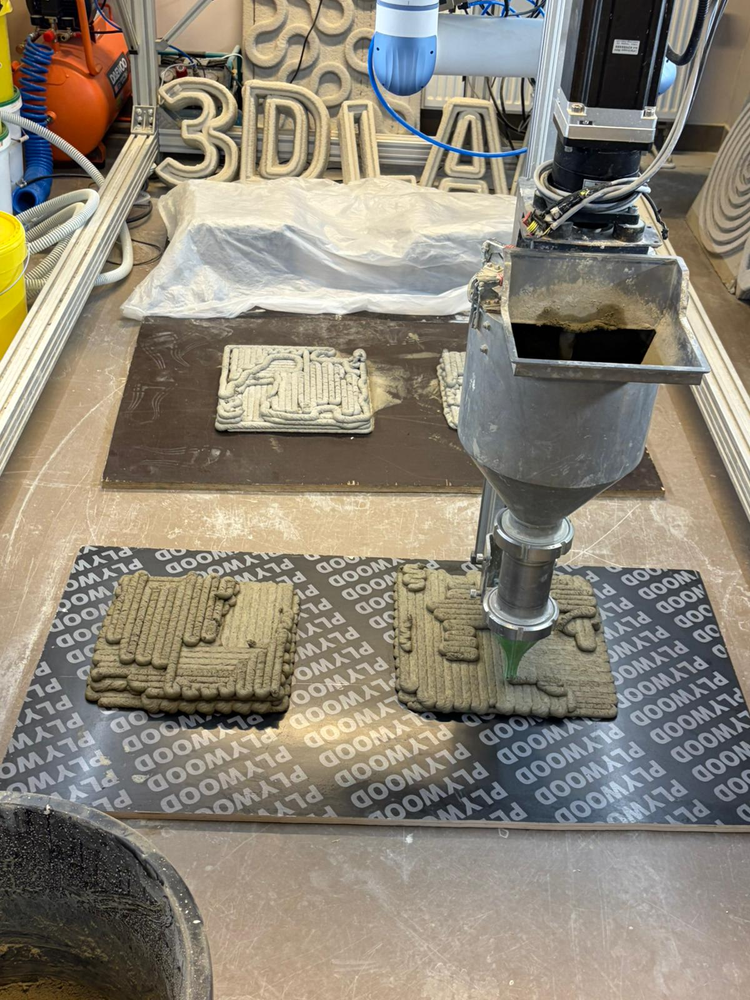

In its early years (even before the BBCE name existed), the team at RTU zeroed in on calcium phosphate bioceramics – substances like hydroxyapatite, the mineral that makes up natural bone. These materials were essentially artificial bone. Over time, as science progressed, the researchers broadened their approach. By the 2010s they were experimenting with composite materials and nanoscale structures to improve bone implants. When BBCE officially launched in 2020, it immediately began embracing emerging technologies: 3D printing to create custom-shaped bone scaffolds, “stealth” nanoparticles to deliver drugs, and even early steps into incorporating living cells into materials . The centre’s focus evolved from just making biocompatible substances to engineering multifunctional implants that actively help the body heal .

What drove this evolution? Partly, it was the march of technology – new tools like 3D bioprinters made once-impossible ideas feasible . Partly, it was real-world medical need: feedback from surgeons pushed BBCE toward personalized solutions, like patient-specific skull plates or dental implants tailored to an individual’s anatomy . And not least, funding and policy nudges (like that EU Teaming project) encouraged BBCE to cover every step from lab research to clinical trials . “From basic ‘artificial bone’ substances to an integrated platform of regenerative technologies” is how one internal report sums up BBCE’s journey . In short, the Centre still focuses on bone regeneration – its bread and butter – but it now casts a much wider net, exploring drug delivery, custom medical devices, and even bioengineering strategies, all aimed at one goal: helping patients recover faster and better.

Despite the serious science, the daily vibe isn’t all test tubes and textbooks. “Some days it’s fun, some days it’s boring – but it’s always curious,” one student intern laughs, describing the ebb and flow of lab life. There are stretches of routine – mixing chemical solutions, monitoring machines – punctuated by flashes of excitement when a new material shows promise (or when someone accidentally blows the lid off a flask). This mix of diligence and surprise seems built into BBCE’s DNA: after all, it’s a place bridging academic rigor with inventive thinking, where even a casual coffee-break joke about “growing bones in jars” might spark a real research idea.

Key Contributions and Breakthroughs

In its short life, BBCE has already notched up scientific achievements that are turning heads in the biomaterials world. One headline-grabbing area is improved bone graft materials. BBCE researchers have developed novel calcium phosphate cements enhanced with bioactive glass – concoctions that harden into bone-like structures and stimulate real bone to grow . By combining the strength of ceramics with the biological perks of bioactive glass, these composite implants could help fractures heal faster and more robustly than before . It’s the kind of arcane lab innovation that, in a few years, might quietly revolutionize how orthopedic surgeons fix broken bones.

Another standout contribution is BBCE’s work in sustainable biomaterials – literally turning trash into medical treasure. In one remarkable project led by Prof. Dagnija Loča, the team is recycling waste eggshells into bone substitutes . Yes, eggshells: those brittle breakfast discards are mostly calcium carbonate, and BBCE scientists found a way to use them as a calcium source for synthesizing amorphous calcium phosphate, a mineral akin to bone tissue . Even the thin membrane inside the shell, usually thrown away, is harvested for proteins that have antibacterial properties . The result is a porous, bone-like ceramic scaffold with enhanced properties – essentially, high-value bone implants made from poultry industry waste . It’s a project that perfectly encapsulates BBCE’s interdisciplinary flair, linking materials science with circular-economy thinking. And it doesn’t hurt that it makes for a great story: “From omelette to orthopedics,” as one student quipped, peering at a jar of eggshell powder in the lab.

Many of BBCE’s breakthroughs are still in the experimental or prototype stage – no, you can’t yet buy an “eggshell bone graft” at your local hospital. But their potential is tremendous. The centre’s innovations could influence how orthopedic and dental implants are made, leading to devices that last longer and integrate better with living tissue . Importantly, BBCE isn’t working in isolation: it has partnered with Latvia’s largest egg producer (to source those eggshells) and maintains close ties with hospitals and industry. By creating a pipeline from lab to clinic, BBCE ensures that a promising material discovered at RTU can swiftly be tested for biocompatibility at LIOS, then tried in preclinical studies via RSU’s medical facilities . This tight feedback loop means viable ideas move forward faster, and unworkable ones are identified early – a fail-fast, learn-fast model that’s new to the region’s traditionally siloed research setup.

Of course, not every idea will pan out commercially, a reality BBCE readily acknowledges. But even the “unsuccessful” experiments add to the trove of knowledge on how to make biomaterials that are both biologically active and patient-tailored, nudging the frontier of regenerative medicine forward . The centre’s staff like to remind visitors (including us curious students) that every claim in their reports is backed by data and citations – a necessity in this cutting-edge field where bold claims must be met with hard evidence . In other words, behind the occasional whimsical lab decor and coffee-pot humor lies a rigorous engine of science, one that’s earning BBCE a place on the world stage of biomaterials research.

Inside the Lab: Methods, Machines, and “Magic”

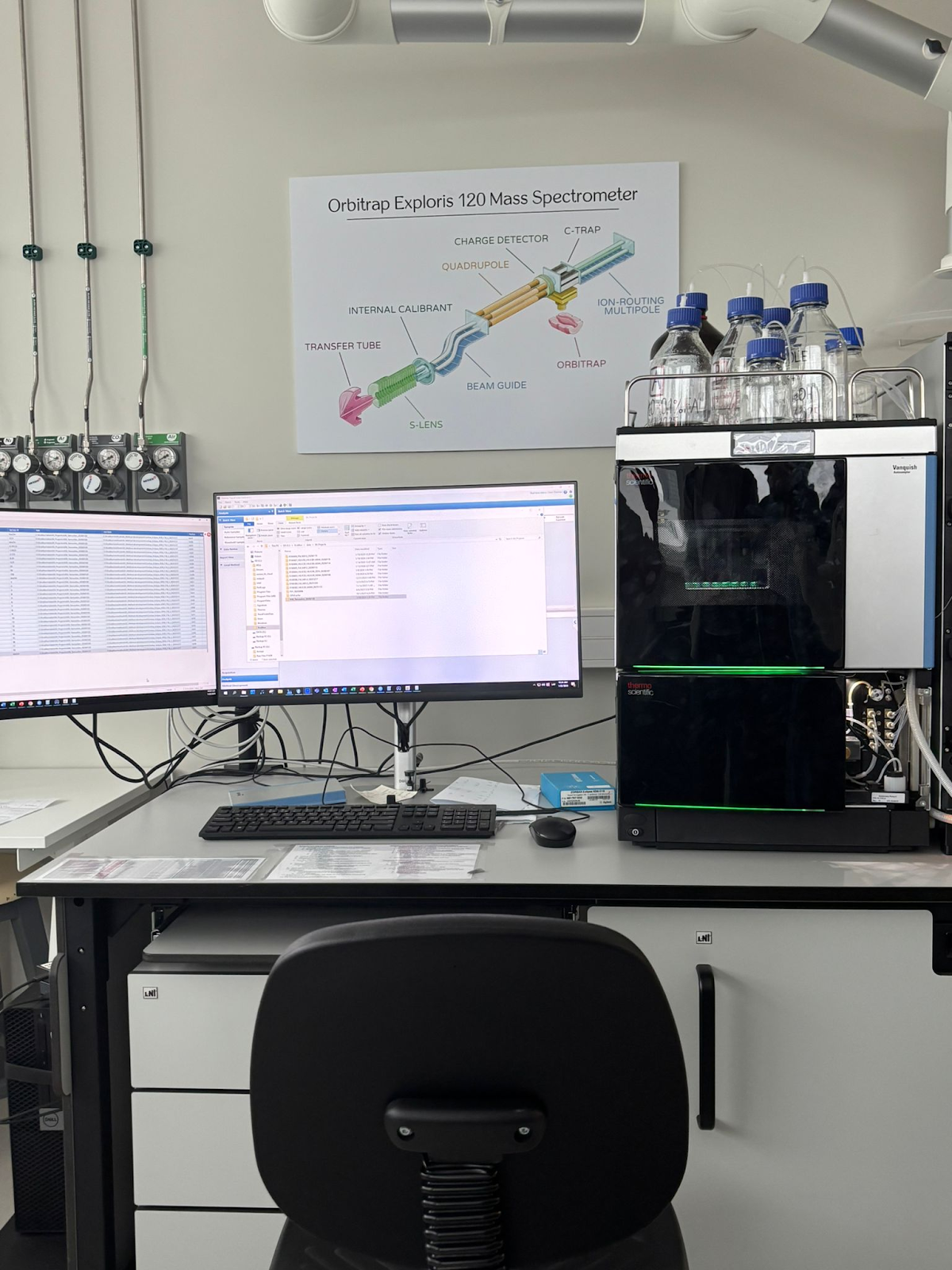

If you toured BBCE’s facilities today, you might be struck by the contrast between how ordinary some equipment looks and how extraordinary the work is. Many of the machines are, to an untrained eye, just boxy metal instruments with flashing lights – yet each is indispensable for crafting the next biomedical breakthrough. The Centre’s new Ķīpsala headquarters, opened in 2025, is a modern glass-and-steel building that consolidates what used to be scattered labs into one high-tech hub . Inside, it houses over 20 state-of-the-art instruments, many unique in the Baltics . Step into one room and you’ll find a hulking X-ray micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) scanner, capable of peering inside a delicate scaffold without destroying it – essentially a 3D X-ray machine to check the tiny pores of a bone implant . In another room sits a scanning electron microscope (SEM) that can magnify surfaces to the nanoscale, revealing whether a coating on an implant is just right . These advanced tools ensure that when BBCE makes a new material, they can inspect it down to the microscopic nooks and crannies, verifying that structure and chemistry are optimized for biological performance .

The work itself is a blend of traditional chemistry and futuristic fabrication. BBCE scientists start by synthesizing materials from the ground up. In a chemistry lab, one might see beakers where calcium and phosphorus solutions precipitate into fine powders – a classic wet-chemistry method for creating calcium phosphate compounds that could serve as bone graft material . Nearby, high-temperature furnaces might be glowing, used to sinter ceramic granules or cure bone cement at over 1000°C . The air smells faintly of heated minerals and solvents; it’s the scent of raw biomaterials in the making. Using sol–gel processing, researchers can also produce bioactive glass or lay down nano-coatings, imparting implants with antibacterial or osteogenic (bone-growing) properties . It’s painstaking work – a tweak in temperature or pH can mean the difference between a material that stimulates healing and one that doesn’t. “We spend weeks perfecting a single recipe,” one PhD student notes while carefully stirring a solution, “making calcium and phosphorus play nice together in acid is not as simple as it sounds!”

Once a new batch of material is prepared, BBCE’s team puts it through its paces. They employ an arsenal of characterization techniques: measuring crystal structures, porosity, mechanical strength, and more. The Centre’s new labs buzz with analysis equipment – X-ray diffractometers to check crystal phases, spectrometers to probe chemical composition, and those aforementioned micro-CT and SEM machines to visualize internal architecture . Often, a sample will ping-pong between instruments for days, generating data. It can be a monotonous process (the “boring” side of research), but as results come in, the excitement grows. A giant whiteboard in the corner fills up with scribbled numbers and graphs; each dataset brings the team closer to knowing if they’ve got a winner or just another iteration to tweak.

One floor up, the focus shifts from chemistry to biology and engineering. Here is where additive manufacturing meets cell science. BBCE proudly operates a 3D bioprinter – a device that looks a bit like an oversized microwave, but instead of heating food, it prints living cells and biomaterials into custom shapes . With this machine, researchers can print a biodegradable scaffold that exactly matches a patient’s bone defect, based on a 3D scan . In one recent demo, we watched wide-eyed as the printer’s nozzle deposited layer upon layer of gel-like material to form a tiny lattice – a prototype scaffold for a jawbone segment, complete with channels where bone cells could settle. The ability to prototype implants in-house within hours is a game-changer for the lab . It allows rapid experimentation (and admittedly, the occasional failed print, whose collapse elicited groans and laughs from the students observing).

Another corner of the lab is devoted to the subtle art of drug delivery. BBCE’s chemists have mastered techniques to encapsulate drugs or ions into porous materials, effectively turning an implant into a slow-release medicine dispenser . For example, they’ve impregnated bone grafts with silver and gallium ions to give them infection-fighting superpowers . They’re also working on those “stealth” nanoparticles – tiny drug carriers designed to evade the immune system . On a computer screen, a researcher shows us a model of a nanoparticle cloaked in special polymers: if successful, it might deliver chemotherapy drugs directly to a bone tumor without getting cleared out by the body’s defenses. It’s intricate, cutting-edge science, but in these labs it becomes almost routine. “Every machine is a box, every box is a mystery,” a postdoc jokes as she opens yet another incubator-looking device. Inside, instead of mystery, we find rows of cell culture dishes – human bone cells being grown to test how they interact with a new material. This brings us to BBCE’s biological work.

Crucially, BBCE doesn’t stop at making materials; it tests them with living cells and even animals to ensure they’re safe and effective. In tissue culture hoods, researchers seed human bone cells onto scaffold samples to see if the cells will cling and thrive . They use confocal microscopes to watch the cells in action, staining them with fluorescent dyes to check for signs of healthy growth . Across town at LIOS (one of the partner institutes), more specialized assays examine whether any toxic substance leaches from the materials. And at RSU’s medical campus, the most promising materials undergo preclinical trials in animal models – for instance, a bioactive bone cement might be used to fill a defect in a rabbit’s femur, to observe how well it encourages new bone formation . BBCE has even set up a dedicated focus group on preclinical biomaterial evaluation to standardize these studies . The pipeline is clear: if it works in the lab dish, try it in a small animal; if it works in the animal, prepare for human trials. It’s a long road from Petri dish to patient, but BBCE’s integrated approach aims to shorten that journey by keeping all the expertise in close collaboration .

For all the sophisticated methodology, a tour of BBCE wouldn’t be complete without soaking in a bit of the culture. In the hallways, framed posters showcase past PhD projects – a gallery of theses on everything from bone cement chemistry to nanofiber scaffolds. It’s a reminder of the academic lineage and the young talent driving the centre’s work. And yes, there’s Jhony the skeleton, eternally grinning in the corner of a seminar room, often adorned with a lab coat for laughs. (He’s a leftover from an old anatomy lab, we’re told, now serving as BBCE’s tongue-in-cheek guardian.) During our visit, we also met researchers from abroad – including a visiting specialist from Austria who led our tour, underscoring BBCE’s international ties. With a core team of around 40 scientists, students, and technicians, the Centre buzzes with multicultural collaboration. One minute you hear Latvian, the next English or German, all spoken over beeping machines and whirring centrifuges. It’s a dynamic, sometimes chaotic environment, but one carefully designed to foster innovation at every turn.

Impact and Future Outlook

In just a few years, BBCE has firmly put Latvia on the map in the biomaterials arena. The Centre’s work is not only yielding academic publications but is seeding what could become a new high-tech industry in the Baltics. By developing know-how in biomaterial implants, drug delivery, and tissue engineering, BBCE is laying the groundwork for a homegrown medical technology sector. The only missing piece, as one observer noted, is a manufacturing partner to commercialize the innovations. Indeed, while no large-scale production has spun out yet, there are promising signs: BBCE’s presence has already attracted interest from foreign biotech companies and inspired new startup ideas in Latvia . In the broader context, BBCE stands as a proof-of-concept for European science policy. It’s frequently touted as a success story of the EU Teaming initiative – evidence that strategic funding and international partnerships can build research excellence in a region previously off the radar .

BBCE’s influence also extends to people – the next generation of scientists and the general public. The Centre has trained numerous new PhD students and postdoctoral fellows since its inception . Many of these young researchers are Latvian, reversing the “brain drain” by giving talent a reason to stay (or return) home for high-impact work. BBCE even runs outreach programs, like the BIO‐GO‐Higher competition for high school students, to spark interest in biomedicine among youth . Such efforts might not yield an immediate patent or paper, but they build a pipeline of human capital essential for sustaining the field. As one of the BBCE team members put it, “We’re not just building better bones; we’re building the people who will build better bones.” In the long run, this may be one of BBCE’s most important contributions – inspiring a culture of innovation and curiosity that outlives any single grant or project.

In conclusion, the Baltic Biomaterials Centre of Excellence has quickly become an anchor institution in Latvian science – a place where history, innovation, and even a bit of humor converge to push healthcare forward . It has accelerated scientific discovery in biomaterials and improved how lab research connects with clinical needs . The new building on Ķīpsala stands as a concrete symbol of progress, but the true impact is in the less tangible things: the collaborations forged, the young minds nurtured, the community of experts and students excited about making the absurd a reality (who else would think to heal bones with eggshells?). As we finish our visit, we pause by Jhony for a final photo. In the shot, the skeleton grins beside us while, in the background, real scientists huddle over a lab bench, discussing the next experiment. It’s a fitting image for BBCE – bridging the gap between the past and the future, the serious and the whimsical, all in service of a very human goal: giving people new ways to heal.

By: Eriks, Alberts, Kristiana, Sofia, Yarik, Mark

About BBCE

Video:

Presentation: